What is that strange bomb in the sky?

That’s what the sailors of the Italian battleship Roma must have wondered in the final moments before they died.

Naval warfare changed on Sept. 9, 1943. Dictator Benito Mussolini had been deposed, the new Italian government was abandoning a lost war and its doomed Nazi ally and the Italian fleet was sailing to Malta to surrender. But the habitually treacherous Nazis, who had always suspected their Italian allies of similar trickery, detected the Italian ships leaving port.

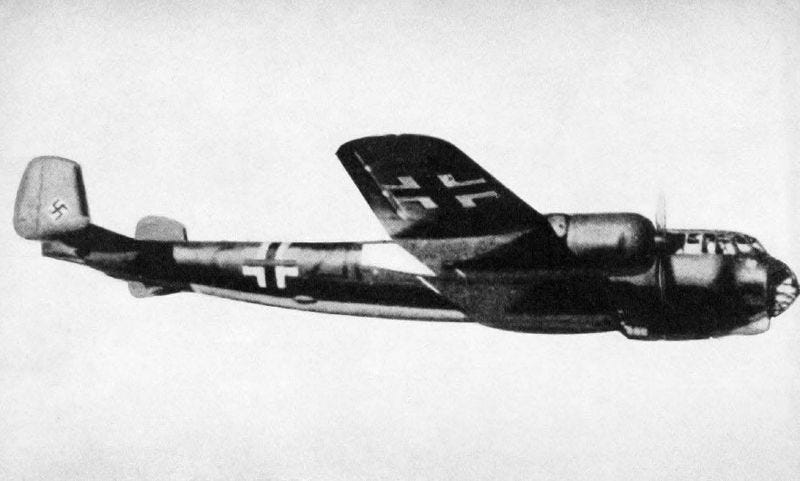

The Luftwaffe dispatched a force of Dornier Do-217 bombers to deal with the Italian ships.

As the bombers approached, the Italians were unsure whether the Germans meant to attack or just intimidate. They were relieved to see the German aircraft appear to drop their bombs into the ocean. Perhaps with uncharacteristic gentleness, the Germans were just firing warning shots.

But then something unexpected happened. Instead of plunging straight down into the sea, the bombs headed toward the Italian ships. One slammed into Roma’s hull, exited out the other side and exploded in the water, destroying an engine room.

A second bomb penetrated the deck into the forward magazine, where shells for the ship’s big 15-inch guns were stored. The battleship exploded, killing 1,253 members of her crew.

The age of the ship-killing missile had dawned.

The first anti-ship smart bombs, invented like so many other weapons by the dark scientists of Nazi Germany, were not just deadly. They seemed inhuman. A “Wellsian weapon from Mars,” was how one newspaper reporter described an early attack.

Smart bombs have become so common in modern warfare that we take them for granted. Yet 70 years ago, a bomb that could chase a ship seemed as exotic and frightening as the muskets of the conquistadors must have seemed to the Aztecs. The Germans “made them [the missiles] turn corners,” an Allied sailor complained.

Anti-ship guided missiles have been used for decades now. Missiles sank the Israeli destroyer Eilat in 1967 and the British destroyer Sheffield in 1982. Today, China hopes that weapons such as the DF-21D ballistic missile, with a range of a thousand miles, can sink U.S. aircraft carriers and thus neutralize American naval power in the Pacific.

But these weapons did not materialize overnight in a Beijing weapons lab. They are the fruits of Nazi research from more than 70 years ago.

A smart bomb named Fritz

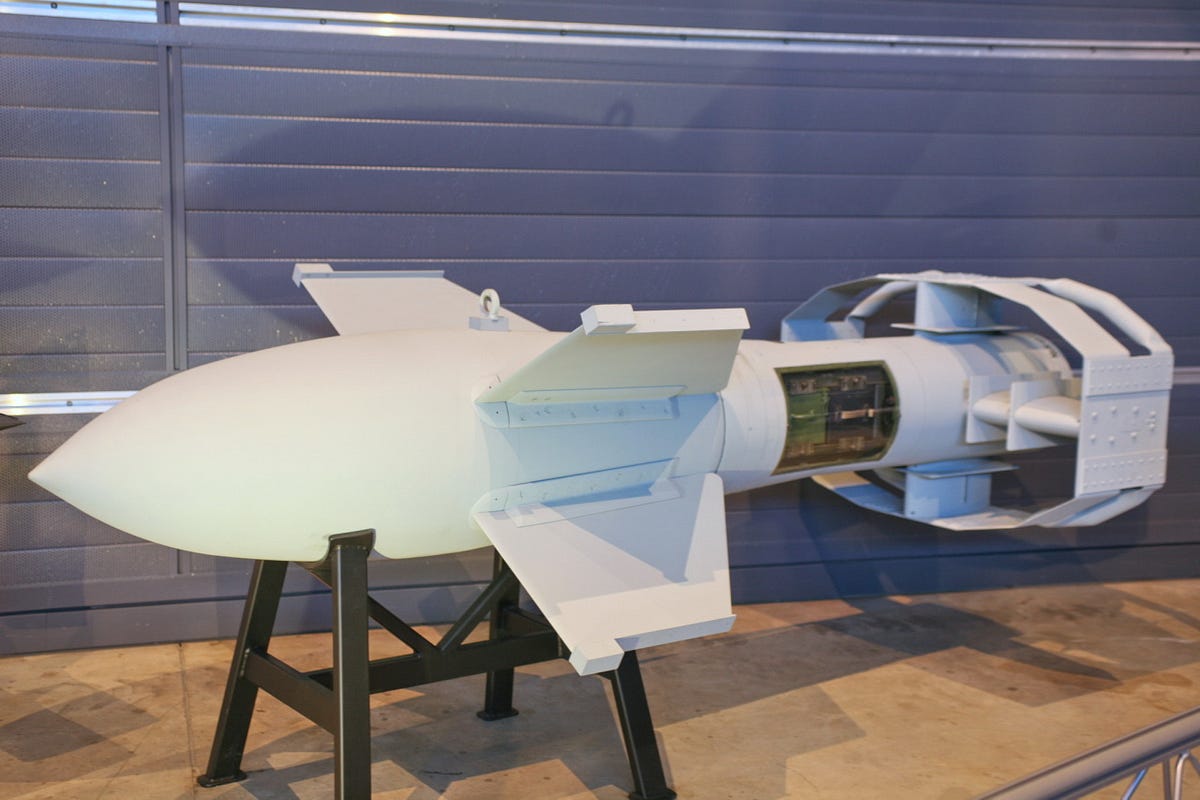

The weapon that sank Roma was known by the very German name Fritz-X. It was not a powered missile but a 3,000-pound armor-piercing gravity bomb meant to be dropped from a bomber at 20,000 feet.

Battleships were armored to survive multiple bomb hits—in 1944, the Japanese super-battleship Musashi was hit by 17 bombs and 19 torpedoes before sinking. But a bomb dropped from high enough should have enough kinetic energy, imparted by gravity, to smash through thick deck armor.

The problem was hitting the battleship in the first place. High-flying bombers in the 1940s had scant chance of hitting a warship frantically weaving through the water at 30 knots. That meant aircraft had to come in low to attack, which made them easier targets for the ship’s antiaircraft guns and also robbed the bombs of kinetic energy.

The 11-foot-long Fritz-X, slung under the wing of a bomber, had radio-controlled fins that could change the munition’s glide path. A tail-mounted flare enabled the operator on the bomber to track and adjust the weapon’s course. Tests showed that 50 percent of bombs would land within five meters of the target—astounding accuracy for the 1940s.

Does this sound familiar? It should, because the concept endures in modern weapon such as America’s Joint Direct Attack Munition, a kit that makes dumb bombs smart by adding fins and satellite guidance.

The Hs 293 missile

The Fritz-X was an awesome battleship-killer, but only under the right conditions. A glide bomb has only gravity rather than a rocket motor for propulsion. The steerable fins on the Fritz-X could adjust its trajectory only slightly, meaning the bomb had to be dropped within three miles of the target.

While deadly to heavily armored warships, the armor-piercing Fritz-X was actually too much bomb for small ships. It would slice all the way through unarmored destroyers and transports and explode in the sea.

The Nazis had another weapon, a genuine anti-ship missile called the Hs 293. The 12-foot-long weapon looked like a miniature airplane with a rocket motor slung underneath.

The radio-controlled Hs 293 could be launched from 10 miles away, out of range of shipboard anti-aircraft guns. Its 2,300-pound high-explosive warhead detonated on contact with a lightly armored ship.

“In a typical deployment, the attacking aircraft would approach the target to within 12 kilometers (6 miles), then fly a parallel course in the opposite direction,” writes Martin Bollinger, author of Wizards and Warriors: The Development and Defeat of Radio Controlled Glide Bombs of the Third Reich.

“When the ship was about 45 degrees off the forward right side, the aircraft launched the HS-293,” Bollinger continues. “The Walther liquid-fueled rocket, running for 10 or 12 seconds, would accelerate to about 600 kilometers per hour (325 knots), at which point the operator had turned the missile into the target.”

“Once the rocket burned out,” Bollinger explains, “the missile continued with its forward momentum, maintaining a glide by virtue of short wings, until the operator steered it into the target.”

The electric razor missile defense

The British and Americans were gravely worried. By the fall of 1943, Allied forces had captured North Africa and Sicily, the U-boat threat was diminishing and the Luftwaffe faded before growing Allied air strength. Now the Brits and Americans could focus on the dangerous task of landing their armies on the European continent.

First they had to thwart the new German ship-killers. The Allies could mostly protect the vulnerable amphibious invasion fleets from regularGerman air attacks. But if German aircraft could stand off at a distance and lob bombs with pinpoint accuracy onto the soft-skinned transports and their escorts, then the Third Reich might stave off invasion.

Fortunately, a disgruntled German scientist had warned the Allies about the smart bombs in 1939, and Ultra code-breakers had intercepted German communications regarding the weapons.

The British outfitted the sloop Egret with special equipment to identify the radio frequencies used to control the German munitions. Some 13 days before Roma was sunk, Egret joined a convoy sailing within range of German bombers based in France.

As hoped, the Germans attacked the convoy with Hs 293 missiles. Unfortunately, one of the ships sunk was Egret.

The Allied landing at the southern Italian port of Salerno on Sept. 3, 1943 was a wake-up call for alliance. The Germans counterattacked and almost drove the Anglo-American troops into the sea. Gunfire from Allied warships saved the landing force … and the entire operation.

But at a terrible cost. The Luftwaffe launched more than 100 Fritz-X and Hs 293 weapons. A Fritz-X struck the famous British battleship Warspite and put the vessel out of commission for months.

Another Fritz-X hit a gun turret on the U.S. light cruiser Savannah and “penetrated through the two-inch armored surface of the turret, tore through three more decks and exploded in the ammunition handling room deep in the bowels of the ship,” Bollinger writes.

Miraculously, Savannah survived—but 197 of her crew did not. German guided weapons sank and badly damaged around a dozen ships off Salerno.

Convoys sailing the Atlantic and Mediterranean also suffered. Convoy KMF-26, whose escort included included two U.S. destroyers equipped with the first anti-missile jammers, was attacked off the Algerian coast on Nov. 26, 1943.

An Hs 293 slammed into the troop transport Rohna, carrying U.S. soldiers to India. At least 1,149 passengers and crew died in what Bollinger describes as the “greatest loss of life of U.S. service members at sea in a single ship in the history of the United States.”

It was not until the 1960s that U.S. authorities even admitted that Rohna had been sunk by a guided missile rather than conventional weapons.

Rumor spread among desperate sailors that switching on electric razors would jam the radio frequencies of the “Chase Me Charlies,” as the British called the guided munitions.

An urgent and massive anti-missile effort ensued. Ships were told to lay down smokescreens so Germans aircrews couldn’t see their targets—and to take high-speed evasive action under attack. But how could anchored transports unloading troops and supplies, or warships providing naval gunfire, maneuver at high speed?

The Allies pinned their hopes on electronic warfare, another class of modern weaponry originating in World War II. The British were already dropping aluminum foil decoys to jam German radars. Less well-known are the Allies’ intensive efforts to disrupt German anti-ship missiles.

Allied agents interrogated captured Luftwaffe aircrew. Recovery teams sifted through missile fragments from damaged ships and examined remnants of bombers left behind on airfields in Italy.

The most intensive work took place in labs across Britain and America including the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, where scientists worked feverishly to jam the radio frequencies used by German missile controllers. operators to control the missiles.

The British chose barrage jamming of multiple frequencies, while the Americans opted for what they considered a more efficient technique of jamming only specific frequencies. The U.S. installed the first jammers on two destroyers in September 1943.

The first anti-missile jammers were primitive and cumbersome by today’s standards. American equipment required multiple operators and devices to identify the correct frequency and match the jammer to the frequency—and do it all in 10 or 20 seconds before the missile hit its target.

Early jammers didn’t work. Based on faulty intelligence, the Allies guessed that the German missiles were controlled by High Frequency signals under 30 MHz. The German actually used the Very High Frequency band of around 50 MHz.

The missiles kept coming.

Yet by August 1944, the Germans missile campaign was over. Some of the last Hs 293s were not even launched at ships, but against French bridges used by Patton’s advancing tank columns. Less than a year after its dramatic debut, the German smart bomb threat disappeared.

No wonder weapon

It’s hard to estimate losses caused by the guided weapons. German air raids saturated Allied defenses by combining smart bomb attacks with conventional dive bomber and torpedo assaults, so it is always not clear which weapon hit a ship.

The Allies also tried to maintain morale by attributing guided weapon losses to conventional weapons.

Bollinger counts 903 aircraft sorties that carried around 1,200 guided weapons. Of those 1,200, almost a third were never fired because the launch aircraft aborted or were intercepted.

Of the remaining 700 weapons, another third malfunctioned. Of the approximately 470 whose guidance systems worked, at most 51—or just over 10 percent—actually hit their targets or landed close enough to damage them.

Bollinger calculates that just 17 to 24 ships were sunk and 14 to 21 damaged.

“At most, only one weapon in 24 dispatched from a German airfield scored a hit or damage-causing near miss,” Bollinger writes. “Only about one in 14 of the missiles launched achieved similar success, and at most one in nine of those known to respond to operator guidance was able to hit the target or cause significant damage via a near-miss.”

“This is very different from the 50-percent hit rate experienced during operational testing,” Bollinger points out.

To be fair, the technology was new. There were no lasers or fire control computers. The Fritz-X and Hs 293 were manually guided all the way. Operators had to track both missile and target through cloud, fog and smoke, without the benefit of modern thermal sights.

“It was virtually impossible to hit a ship that was steaming more than 20 knots and could fire back,” Bollinger tells War is Boring. “Almost all of the hits were against slow and/or defenseless targets.”

Bollinger hypothesizes that a phenomenon called “multi-path interference,” unknown at the time, may also have hampered the performance of the Hs 293. Radio command signals sent from the bomber to the missile might have overshot the weapon, bounced off the ocean surface below and interfered with the missile guidance signal.

The early jammers were ineffective, but Bollinger believes that by the time of the Normandy assault in June 1944, the equipment had improved enough to offer a measure of protection—and partly explains why German missiles performed poorly later in the war.

Strangely, while the Germans took measures to counteract Allied jamming of their air defense radars, they never really addressed the possibility that their anti-ship missiles were also being jammed.

It’s wrong to blame the bomb for the faults of the bomber. The real cause for the failure of German smart bombs was that by the time they were introduced in late 1943, the Luftwaffe was almost a spent force.

Already thinly spread supporting the hard-pressed armies in Russia and the West, the German air arm suffered relentless bombardment by U.S. B-17s and B-24s. The Third Reich could never deploy more than six bomber squadrons at a time equipped with the Fritz-X and Hs 293.

When the Luftwaffe ruled the skies over Poland and France in 1939, this might have been enough. By late 1943, a guided-bomb run was practically suicide.

German bombers making daylight attacks had to run a gauntlet of fighters protecting Allied ships in the daytime. Night attacks were marginally safer for the bombers but still exposed them to radar-equipped British and American night fighters. The Allies aggressively bombed any airfield suspected of harboring the smart bombers.

“Allied fighter air cover was by far the most important factor,” Bollinger tells War is Boring. “Not only did it lead to large numbers of glide-bombing aircraft getting shot down, it also forced the Germans to shift missions from daylight to dusk or nighttime. This in itself lead to a major and measurable reduction in accuracy.”

Many raids would cost the Germans a few bombers. By the standards of the thousand-bomber raids over Germany, this was trifling. But for the handful of specially trained and equipped Luftwaffe squadrons, it was catastrophic.

Of the 903 aircraft sorties, Bollinger estimates that in 112 of them, the bombers were lost before launching their weapons. Another 21 were shot down or crashed on the return flight, for an overall loss ratio of 15 percent.

“Each time a pilot departed on a glide bomb mission, he had almost a one-in-seven chance of never returning in that aircraft safely,” Bollinger says. “Put another way, the probability that a pilot would return safely after each of the first 10 missions was only 20 percent.”

Learning from history

The rise and fall of the Nazi anti-ship missiles offers lessons for the U.S. and its opponents in the present day. American planners worry that smart anti-ship weapons in the hands of China, smaller nations like Iran or even insurgent groups could threaten U.S. warships and amphibious forces.

One lesson from the 1940s is that passive defenses such as jamming have limited utility against access denial weapons. The best defense is to destroy the launch vehicle before it can fire. “Kill the archer” is the term the Pentagon uses.

China stands to learn the most profound lesson. For all the power and terror of the German anti-ship weapons, they could not compensate for the inability of the German navy and Luftwaffe to confront the Allied navies on the open seas.

Smart bombs did worry Allied commanders, but the new munitions couldn’t prevent the amphibious invasions of Italy and France. Chinese missiles might disrupt U.S. operations, but they are no substitute for countering a powerful navy with an effective navy of your own.

Perhaps the biggest lesson of all is that what is new is old. With each passing year, the weapons of World War II seem closer to the era of Gettysburg and Jutland than the high-tech warfare of today. That perception can encourage an unjustified smugness.

The problems modern navies and air forces struggle with—anti-ship guided missiles, jamming, operations in contested airspace—were the same that German pilots and Allied sailors faced.

The terror that the crew of an Italian battleship, British cruiser or American merchant ship felt at the sight of German missiles might not differ from what a U.S. destroyer or carrier crew might feel while being targeted by Chinese ballistic missiles.SOURCE:war-is-boring

No comments:

Post a Comment